Trying to understand energy crisis related discussions can be daunting: abbreviations, technical concepts and lots of background data is often assumed to be understood by each participant.

Let's look at an example.

Many people believe in PO, due to multiple modeling techniques showing a Hubbert Peak within the next 10-13 years for total liquids in the world. Yes, there has even been peer-reviewed scientific papers on the subject.

In plain English: We can't grow our daily oil production rate indefinitely. Daily oil production rate will likely peak before the year 2020. When production peaks, demand will exceed supply. Many engineers and scientist have studied this. A lot of them agree on the time of peaking.

Now, why is that a problem? According to the Hirsch Report, the minimum mitigation time before peak is 20 years. It is highly probable we have less time available than that. According to most grim estimates, only one fourth of that. There are oil industry insiders and energy bankers who have claimed we may be at peak now. Supply-demand gap is incredibly thin, cushions are gone. Demand has already exceeded supply in poorer areas.

Plain English: Changing cars, trucks, planes, boats and generators to run on electricity takes 20 years or more. Demand for oil may greatly exceed oil supply well before that. Many experts say we can't increase our daily oil production anymore. This means we are at production peak now. Some countries are already experiencing oil shortages. In Africa, oil shortages are happening today.

What would we do, if we had 20 years? Many say "biofuels".

A lot of scientists are increasingly weary of bio-fuels, due to EROEI being proven very low and sustainability of fuels being in doubt (mp3). Also, there's a significant scaling challenge as well in production of bio-fuels.

Bio-fuels may take more energy to make than what they give. Making bio-fuels will not help us supplant fossil oil. Also, bio-fuels may not cut greenhouse gases. Further, bio-fuels may not be available in as huge volumes as we use fossil oil.

CTL and GTL fuels have their own scaling issues and the GHG impact is considerable. Also, there's that nasty issue of overall hydrocarbon resource depletion.

So, even if successful, alt-fuels will only provide a small wedge, not a replacement for fossil oil.

That means, PO is mostly a liquid fuel crisis.

We can only make a bit of oil from coal or gas. This will not be sufficient to cover our oil demand. Also, coal and gas based alternative fuels cause additional greenhouse gas emissions. Further, the amount of natural gas and coal reserves we have left is uncertain. We will need lots of different new liquid fuels to replace diminishing oil. We face a shortage of liquid fuels. A crisis of energy in liquid form.

Now, what is a likely scenario in this crisis?

Short term, one must factor in two important issues, on physical, another economical:

- Falling net energy of oil production, due to diminishing API and increasing sulfur ratio, not to mention increased discovery, drilling and pumping energy costs. This results in a compound upward price pressure on top of the normal resource shortage.

- ELM. Available exports fall faster than production. This may result in shortages and certainly raises the prices even further.

The rest of the oil we have left is of increasingly worse quality. It takes more energy to pump it out of ground. It takes even more energy to make it usable diesel and gasoline. Rising energy costs will raise the price of remaining oil, even if demand stayed steady. However, demand is rising, not staying steady, so it also adds to rising energy prices.

Export Land Model (ELM) studies how much oil is exported. Majority of oil production in the world is in the hands of less than a dozen producers. With most of them, their domestic oil consumption is growing faster than their oil production. When their oil production starts to peak, they will need more of the oil for domestic production. As a result, producers will export less oil. This exported oil is what dictates the price of oil on the world market. It also dictates whether people in oil consuming countries have oil to use at all. If producers do not export, consumers cannot buy. Whatever the price.

What could these issues lead to? Nobody knows, but several obvious causalities have been suggested by various authors:

A lot of things are already taking place and it is likely that the trends will intensify for the foreseeable future.

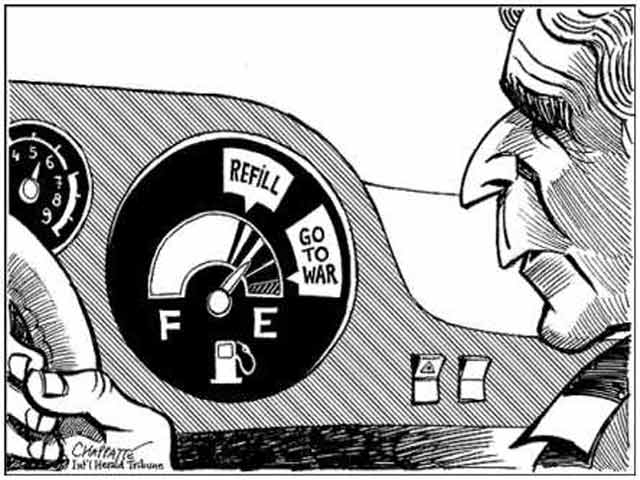

Some argue that as oil demand greatly exceeds supply: countries will go to war for oil. More food will be turned into bio-fuels. This will result in food shortages in poorer countries. Oil dependent African and Asian countries will experience electricity blackouts. Purchase of oil will be rationed. Oil may unexpectedly run out for a while. Natural gas, coal and electricity will be used more to help with oil shortage. Prices of coal, gas and electricity will rise. Countries will start to build more nuclear power plants. Not enough nuclear power plant makers exist to make plants for all who want them. Price of uranium will continue to rise.

Of course, there would be ways to solve supply-demand gap.

Let's first look at the options that are unlikely to work other than as minor temporal mitigation wedges:

Technology breakthroughs do not create energy out of nothing. When oil starts to run out, more energy is needed. Available energies include nuclear, wind, solar, tide and

geo-thermal. These can supplant some of the needed oil. However, there is no single technological fix or alternative source will make the problem go away quickly. Transition to alternative energy sources will take time. Some of the alternatives are likely to fail (e.g. 1st and 2

nd generation

biofuels). Some alternatives are just too expensive in terms of price (2

nd and 3rd generation

biofuels). Some just do not make any physical sense (e.g. hydrogen production via electrolysis).

Energy efficiency increases are useful in the short run. On the long run efficiency savings are lost in increased energy use. It is difficult to conserve oneself out of the liquid fuel crisis problem. At least, it is impossible to do it without harming economic growth and current global trade.

Other, more systemic solutions have been proposed, such as CJP's Oil Depletion Protocol also known as the Rimini Protocol, which is these days promoted by RH, who also advocated powerdown.

However, due to the pessimistic mode of many of PO thinkers (doomers), ODP is not seen as a very realistic option.

Oil depletion protocol states makes countries to reduce their oil consumption at the same rate that world oil production diminishes. Protocol requires that the countries sign and abide by it. Currently no large oil using country has written the Oil depletion protocol. Many believe that nation states are more likely to price bid or go to war for oil. States are unlikely to voluntarily reduce their consumption.

Doomer is a person who thinks that the current economic status

quo and

wellbeing of the world is not sustainable. A

doomer thinks that oil production peak will result in a doom of the civilization. In the diminished version,

doomer thinks that oil peak a radically restructures the world society.

Many, in fact (yours truly excluded) believe in some sort of a cataclysmic overshoot collapse, like forecast by th Olduvai Theory. Some even believe the thermo/gene collision is the inescapable future of mankind.

Some people Peak oil will result in the collapse of the known civilization. Arguments are based on exceeding the carrying capacity of earth. Only stored energy (such as oil) has enabled humans to exceed carrying capacity temporarily. When that energy is used up (non-renewable), carrying capacity limits will be met.

But let's take a deep breath. No need to skip peak oil stages.

Don't paralyze yourself. Nobody has a crystal ball. Forecasters have been wrong before. No need for doomer-porn.

Malthus was already wrong over a hundred years ago. Or at least he was off with his timing, because he didn't factor in hydrocarbon resources, such as oil, coal and natural gas. Those postponed the peak at least a hundred years. People who love to think pessimistically about peak oil, will often indulge in scenarios of

dystopia. Consuming such scenarios in large doses may not be healthy for one's mental state.

So, what is there to do?

ELP, is one option. Permaculture another. Relocalization a third one.

Economize, Localize and Produce. Make do with what you really need. Start acting and consuming locally to conserve energy. Become less dependent on things from afar, whether food, services or work. Start producing things basic things that are needed and valuable.

Permaculture guides one in sustainable living.

Relocalization is an effort to start up and develop local community actions.

Oh, why are techno-fixes unlikely to work? In the old tradition of Finnish math books, the proof is left as an exercise for the reader.